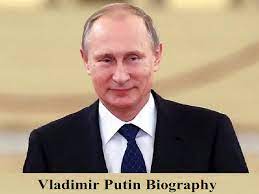

Vladimir Putin Biography

The current president of Russia is Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, a politician and former intelligence officer who was born on October 7, 1952. Since 1999, Putin has held both the positions of president and prime minister continuously: from 2000 to 2008 and since 2012, he served as president.

Before leaving his position as a KGB foreign intelligence officer in 1991 to start a political career in Saint Petersburg, Putin worked there for 16 years, attaining to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In order to work in President Boris Yeltsin’s government, he relocated to Moscow in 1996. Before being named prime minister in August 1999, he held the positions of secretary of the Russian Security Council and director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) for a brief period of time. Following Yeltsin’s resignation, Putin took over as president in an interim capacity before winning the general election for his first term less than four months later. In 2004, he won reelection.

In order to fulfill his constitutionally mandated cap of two consecutive terms as president, Putin served as prime minister once more under Dmitry Medvedev from 2008 to 2012. In a presidential election characterized by protests and suspicions of fraud, he won reelection in 2012 and again in 2018. He signed constitutional modifications into law in April 2021 following a vote, one of which would allow him to seek for reelection twice more, perhaps extending his term as president to 2036.

Following economic reforms and a fivefold increase in the price of oil and gas, the Russian economy increased by an average of seven percent annually during Putin’s first term as president. Putin also led Russia in a conflict with Chechen separatists that restored federal rule over the territory. He managed military and police reform while serving as prime minister under Medvedev. Russia funded a war in eastern Ukraine during his third term as president, annexing Crimea, which led to international sanctions and a financial crisis in Russia.

In addition, he authorized military action in Syria to back Bashar al-Assad, an ally of Russia, in the country’s civil war. This action led to an agreement that granted permanent naval ports in the Eastern Mediterranean. In February 2022, during his fourth term as president, he started a sizable invasion of Ukraine, which sparked worldwide outrage and greatly increased sanctions. He declared a partial mobilization in September 2022 and violently seized four Ukrainian oblasts into Russia. In conjunction with his alleged criminal culpability for wrongful kidnappings during the conflict, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin in March 2023.

Russia has regressed to authoritarianism and lost its democratic gains under Putin’s leadership. His leadership has been marked by pervasive human rights violations and persistent corruption, including the detention and harassment of political opponents, the intimidation and repression of Russia’s independent media, and the absence of free and fair elections. Putin’s Russia had low rankings on the Corruption Perceptions Index from Transparency International, the Democracy Index from the Economist Intelligence Unit, the Freedom in the World Index from Freedom House, and the Press Freedom Index from Reporters Without Borders. After Belarus’ Alexander Lukashenko, Putin has been president of Russia for the longest and is now the president of Europe with the second-longest tenure.

Vladimir Putin Early life

Putin was the youngest of Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin’s three children and Maria Ivanovna Putina’s (née Shelomova; 1911-1998) three children when he was born on October 7, 1952, in Leningrad, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia). Spiridon Putin (1879–1965) served as Joseph Stalin’s and Vladimir Lenin’s personal chef. Two brothers died before Putin was born: Viktor, born in 1940, died of diphtheria and malnutrition in 1942 during the Nazi German forces’ siege of Leningrad, and Albert, born in the 1930s, perished in infancy.

Putin’s father served as a conscript in the Soviet Navy’s submarine fleet in the early 1930s, and his mother worked in a factory. His father was a member of the NKVD’s destruction brigade during the initial stages of Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. He was afterwards sent to the regular army, where he suffered a serious injury in 1942. In 1941, the German occupants of the Tver region assassinated Putin’s maternal grandmother, and during World War II, his maternal uncles vanished on the Eastern Front.

Vladimir Putin Education

Putin began attending School No. 193 on Baskov Lane, not far from his house, on September 1, 1960. He was one of the few students in his class of roughly 45 students who had not joined the Young Pioneers yet. He started doing sambo and judo at the age of 12. He cherished reading the writings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Lenin in his spare time. Putin speaks German fluently and has studied the language at Saint Petersburg High School 281.

Putin received a law degree in 1975 from Leningrad State University named for Andrei Zhdanov (now Saint Petersburg State University). “The Most Favored Nation Trading Principle in International Law” was the topic of his thesis. He was compelled to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) while he was there, and he remained a member of it until its dissolution in 1991.

Putin had a meeting with Anatoly Sobchak, a corporate law assistant professor who went on to co-author the Russian constitution and corrupt practices in France. Sobchak would have an impact on Putin’s career in Moscow, and Putin would have an impact on Sobchak’s career in Saint Petersburg.

At the Saint Petersburg Mining University, he earned his Ph.D. in economics (Candidate of Economic Sciences) in 1997 for a thesis on the strategic planning of the mineral sector.

Vladimir Putin Early career

Putin attended Leningrad State University to study law, and Anatoly Sobchak served as his professor there. Sobchak went on to become a prominent reformer during the perestroika era. Putin worked for the KGB (Committee for State Security) for 15 years as a foreign intelligence agent, spending six of those years in Dresden, East Germany. He left active KGB duty in 1990 with the rank of lieutenant colonel and relocated back to Russia to take the position of prorector of Leningrad State University, where he was in charge of the university’s external contacts. Soon after, Sobchak, St. Petersburg’s first democratically elected mayor, hired Putin as his advisor. He rapidly gained Sobchak’s trust and developed a reputation for getting things done; by 1994, he had attained the position of first deputy mayor.

Putin relocated to Moscow in 1996, where he worked as Pavel Borodin’s assistant on the presidential staff. Anatoly Chubais, a fellow Leningrader, and Putin became close as he advanced in administrative roles. Putin was appointed director of the Federal Security Service (FSB; the domestic KGB replacement) by President Boris Yeltsin in July 1998. Shortly after, he was appointed secretary of the powerful Security Council. Putin was made prime minister in 1999 by Yeltsin, who was looking for a successor to take over his position.

Putin’s popularity increased despite the fact that he was essentially unknown when he began a well-planned military operation against Chechen separatist insurgents. The Russian public, worn out by years of Yeltsin’s unpredictable behavior, admired Putin’s composure and decisiveness under duress. Unity, a new political force, won the December parliamentary elections thanks to Putin’s backing.

First and second terms as president of Russia

Yeltsin abruptly announced his resignation on December 31, 1999, and appointed Putin as acting president. The austere and restrained Putin easily won the elections in March 2000 with around 53% of the vote, promising to restore a battered Russia. As president, he aimed to eradicate corruption and establish a tightly controlled market economy.

By separating Russia’s 89 regions and republics into seven new federal districts, each of which is led by a delegate chosen by the president, Putin quickly reasserted his authority over the country. The ability of regional governors to sit in the Federation Council, the upper house of the Russian parliament, was also taken away by him. Putin took action to curtail the influence of Russia’s unpopular financiers and media moguls—the so-called “oligarchs”—by shutting down a number of media outlets and initiating legal action against other influential people. In 2002, Putin declared the military war over, although losses were still high. He faced a challenging situation in Chechnya, particularly from rebels who launched terrorist attacks in Moscow and guerilla attacks on Russian troops from the region’s mountains.

Putin vehemently disagreed with George W. Bush’s 2001 decision to renege on the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. He offered the use of Russian airspace for humanitarian deliveries and assistance in search-and-rescue operations in reaction to the September 11 attacks on the United States in 2001. He also guaranteed Russia’s support and cooperation in the U.S.-led effort against terrorists and their allies. Nevertheless, in 2002–2003, Putin sided with French President Jacques Chirac, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, and others to reject American and British intentions to overthrow Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq.

In March 2004, Putin was handily reelected as president, presiding over an economy that had experienced revival following a protracted recession in the 1990s. In the parliamentary elections held in December 2007, Putin’s party, United Russia, garnered a resounding victory. The results confirmed Putin’s authority even though international observers and the Communist Party of the Russian Federation questioned the fairness of the elections. In 2008, after being required to do so by a constitutional clause, Putin appointed Dmitry Medvedev to succeed him.

Putin as prime minister

In a timely manner following Medvedev’s resounding victory in the presidential election of March 2008, Putin made it known that he had agreed to lead the United Russia party. Within hours of assuming office on May 7, 2008, Medvedev chose Putin as the nation’s prime minister, fulfilling overwhelming expectations. The following day, the appointment was confirmed by the Russian parliament. Putin was still seen as the major force within the Kremlin, despite the fact that Medvedev became more assertive as his time went on.

Despite rumors that Medvedev may seek reelection, he declared in September 2011 that he and Putin would switch roles if United Russia won the election. A wave of public outrage was brought on by widespread irregularities in the parliamentary elections held in December 2011, and Putin found himself up against an unexpectedly potent opposition movement. Putin, however, won a third term as president of Russia on March 4, 2012. Putin handed over leadership of the party to Medvedev by stepping down as chairman of United Russia before to his inauguration. On May 7, 2012, he took office as president, and one of his first official acts was to name Medvedev as prime minister.

Third presidential term of Vladimir Putin

Attempts to quell the protest movement were mainly effective during Putin’s first year back in office as president. Opposition leaders were imprisoned, and nonprofit organizations that received funds from overseas were referred to as “foreign agents.” When U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden sought asylum in Russia after disclosing the existence of a number of top-secret NSA programs, relations with the United States deteriorated in June 2013.

Putin stated that Snowden may stay in Russia as long as he stopped “bringing harm to our American partners.” In August 2013, following chemical weapons incidents outside of Damascus, the United States argued for military intervention in the Syrian Civil War. Putin advocated moderation in a New York Times editorial, and American and Russian diplomats mediated a deal calling for the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons stockpile.

Putin ordered the release of over 25,000 prisoners from Russian jails in December 2013 to mark the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the post-Soviet constitution. Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the former leader of the Yukos oil giant who had been imprisoned for more than ten years on accusations that many people outside of Russia felt were politically motivated, was also pardoned by him in a separate action.

The Ukraine conflict and Syrian intervention

Viktor Yanukovych’s government in Ukraine was deposed in February 2014 as a result of months of persistent protests, and Yanukovych fled to Russia. Putin asked parliament for permission to send troops to Ukraine to protect Russian interests while refusing to accept the legitimacy of the interim administration in Kyiv. Early in March 2014, Crimea, an autonomous republic of Ukraine with a predominance of Russian ethnicity, was effectively under the authority of Russian troops and pro-Russian paramilitary forces.

Residents of the Crimea chose to join Russia in a popular referendum on March 16, and Western governments responded by imposing a number of travel restrictions and asset freezes on Putin’s close associates. On March 18, Putin signed a treaty merging the peninsula into the Russian Federation, claiming that it had always been a part of Russia. The U.S. and the EU imposed economic sanctions on more of Putin’s political friends in the days that followed. Putin signed legislation on March 21 to formally annex Crimea after the treaty was approved by both houses of the Russian parliament.

Armed conflict between the Kyiv administration and unidentified gunmen was started in April 2014 when they took control of government facilities across southeast Ukraine while wearing Russian equipment. Although all indications led to direct Russian involvement in the insurgency, Putin resolutely denied having a hand in the conflict and referred to the area as Novorossiya (“New Russia”), invoking claims from the imperial era.

When Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17, carrying 298 passengers, crashed in eastern Ukraine on July 17, 2014, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that a Russian-made surface-to-air missile fired from rebel-held territory was to blame. Western nations tightened the sanctions system in response, and these actions, along with the sharp decline in oil prices, severely damaged the Russian economy. When the leaders of Russia and Ukraine gathered for cease-fire negotiations on September 5 in Minsk, Belarus, NATO believed that more than 1,000 Russian soldiers were engaged in active combat within Ukraine. The bloodshed was reduced by the cease-fire but was not entirely stopped, and pro-Russian separatists spent the next months driving Ukrainian government forces back.

Putin and other international leaders convened in Minsk on February 12, 2015, to agree a 12-point peace plan intended to put an end to the conflict in Ukraine. Despite a brief lull in the violence, it resumed in the spring, and by September 2015, the United Nations (UN) reported that 8,000 people had died and 1.5 million had been forced to flee their homes as a result of the war. In a speech to the UN General Assembly on September 28, 2015, Putin outlined his vision of Russia as a global power that is able to project its influence overseas, while portraying the US and NATO as dangers to international security.

When Russian aircraft attacked targets near the towns of Homs and Hama, two days later, Russia actively joined the Syrian Civil War. Russian defense officials said that the airstrikes were meant to hit ISIL (Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant) personnel and equipment, but it appears that Bashar al-Assad’s foes in Syria, who are also Russian allies, were the main targets.

Silencing critics and actions in the West

Opposition leader Boris Nemtsov was shot and killed on February 27, 2015, just days after speaking out against Russian involvement in Ukraine. The shooting occurred in close proximity to the Kremlin. Nemtsov was simply the most recent Putin critic to be murdered or pass away under questionable circumstances. A British public investigation officially charged Putin in January 2016 with killing former Federal Security Service (FSB; the KGB’s replacement) officer Alexander Litvinenko in 2006. Litvinenko was polonium-210 poisoned while sipping tea in a London hotel bar. Litvinenko has previously spoken out against the Russian government’s connections to organized crime both before and after his defection to the UK.

The two individuals accused of carrying out the assassination were extradited by Britain, but both denied involvement, and one—Andrey Lugovoy—had subsequently been elected to the Duma and was now protected from prosecution by parliamentary privileges.

Aleksey Navalny, a prominent opposition activist who helped organize the 2011 protests, was frequently detained on what his supporters claimed were politically motivated allegations. Navalny came in second place in the 2013 vote for mayor of Moscow, but his Progress Party was barred from participating in the subsequent elections due to procedural issues. The lowest voter turnout since the breakup of the Soviet Union occurred in the parliamentary election of September 2016.

Putin’s consistent implementation of so-called “managed democracy,” a system in which the fundamental institutions and processes of democracy were preserved but the results of elections were essentially predetermined, was blamed for voter apathy. Election observers found numerous irregularities, such as instances of ballot stuffing and repeat voting, but Putin’s United Russia party nonetheless declared victory. Due to its registration status, Navalny’s party was unable to run any candidates, and Nemtsov’s PARNAS garnered less than 1% of the vote.

Putin’s participation in Syria had altered the balance of power by 2016, and it became clear that Russia was waging a massive hybrid warfare operation with the aim of undermining the authority and legitimacy of Western democracies. While some of the attacks resembled blatant Soviet interventionism during the Cold War, others blurred the boundary between cyberwarfare and cybercrime. Hundreds of thousands of people were left in the dark as a result of two sophisticated cyberattacks on the Ukrainian power grid and frequent violations of NATO airspace in the Baltic by Russian fighter jets. Ukrainian Pres.

Almost every sphere of Ukrainian life was targeted in more than 6,000 cyberattacks over a two-month period, according to Petro Poroshenko’s assessment. Poroshenko claimed that the cyberwar campaign had been connected to Russian security agencies by Ukrainian investigators. Authorities in Montenegro, where the pro-Western government was getting ready to join NATO, narrowly avoided a conspiracy to kill Prime Minister Milo ‘jukanovi’ and replace him with a pro-Russian one. Prosecutors in Montenegro discovered a plot that allegedly involved two Russian intelligence officers, nationalist Serbs, and rebels who supported Russia in eastern Ukraine.

A number of high-profile hacking attempts that were launched in the months before the 2016 U.S. presidential election targeted the Democratic Party and its contender for president, Hillary Clinton. Computer security professionals linked these intrusions to Russian intelligence services, and in July 2016, WikiLeaks released thousands of private emails. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation launched an investigation into Russian attempts to sway the presidential election within days.

Later it emerged that this probe was also looking at any links between those efforts and Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Trump later challenged Russia to “find [Clinton’s] 30,000 missing emails” after joking that Russia had released the stolen emails because “Putin likes me.” Despite these claims, Trump consistently denied that Putin was attempting to influence the election in his favor.

Following Trump’s unexpected victory in November 2016, the cyberattacks and potential Russian involvement with Trump’s campaign team drew fresh attention. Putin had directed a multifaceted operation to sway the election and erode confidence in American democratic systems, according to U.S. intelligence services. President Barack Obama of the United States slapped economic sanctions on Russian intelligence services and dismissed hundreds of alleged Russian operatives, but President-elect Donald Trump persisted in disbelieving their findings. The U.S. Congress launched new investigations after Trump took office in January 2017 to look into the type and scope of Russian interference in the presidential election.

Putin, for his part, denied that any effort had been made to sway elections elsewhere. But in May 2017, a different cyberattack was traced to Fancy Bear, the organization with ties to the Russian government that had hacked the Democratic Party. Finalists in the second round of France’s presidential election were the centrist Emmanuel Macron and the far-right Marine Le Pen of the National Front.

Le Pen, who had previously received financial backing from a bank with connections to the Kremlin, vowed to work to have the sanctions regime put in place following Russia’s annexation of Crimea lifted. A vast collection of internal correspondence known as “MacronLeaks” appeared online only hours before a media embargo on campaign-related news coverage took effect. This attempt was in vain because Macron defeated Le Pen and won the presidency of France with almost twice as many votes.

Despite Russia’s slow economy and pervasive government corruption, Putin’s foreign policy appeared to pay off significantly at home, as his public popularity rating constantly hovered around 80%. Low oil prices and Western sanctions added to the country’s already bleak financial picture, and international investors continued to be wary of risking their money in a place where loyalty to Putin was valued more highly than upholding the law. Even after Russia experienced a recession for seven consecutive quarters, consumer consumption and salaries were unchanged in 2017. These and other internal concerns didn’t seem to have much of an impact on Putin’s reputation; among those who expressed concern about these problems in opinion surveys, Dmitry Medvedev received the greatest blame.

Vladimir Putin Fourth presidential term

Salisbury novichok attack and relationship with Trump

The outcome of Putin’s bid for a fourth term as president appeared all but guaranteed as the March 2018 election drew near. Navalny, the opposition’s public face, was disqualified from running, while Pavel Grudinin, the Communist candidate, came under constant fire from the state-run media. When Sergei Skripal, a former Russian intelligence officer who had been convicted of spying for Britain before being released to the UK as part of a prisoner swap, was discovered unconscious with his daughter in Salisbury, England, two weeks before the election, Putin found himself at the center of a significant international incident.

The two allegedly came into contact with a “novichok,” a sophisticated nerve toxin created by the Soviets, according to investigators. Theresa May, the British prime minister, removed around two dozen Russian intelligence agents who had been operating in Britain under diplomatic cover after British officials suspected Putin of ordering the attack.

On March 18, 2018, Russians went to the polls, and the diplomatic dispute had not subsided. Not by chance, the occasion was the fourth anniversary of Russia’s acquisition of the Crimean Autonomous Republic, which gave Putin a boost in domestic popularity. Putin, as predicted, won a resounding victory in an election that the independent election watchdog Golos deemed to be replete with anomalies. Voter fraud was widely reported, and Putin had hoped for a bigger turnout than in his 2012 election victory. The outcome was hailed by Putin’s campaign as a “incredible victory.”

On July 16, 2018, Putin and Trump had a summit meeting in Helsinki. This was soon after Russia’s well-received staging of the World Cup. They had spoken at the 2017 Group of 20 (G20) summit in Hamburg, Germany, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Da Nang, Vietnam, but this was their first official one-on-one meeting. It happened towards the conclusion of Trump’s tour to Europe, during which he had strained ties with other countries.

traditional allies in Europe. Trump stated that he believed his meeting with Putin would be the “easiest” of his trip, despite the concerns of some observers who questioned whether Trump would be able to hold his own in negotiations with a counterpart as experienced and wary as Putin.

Putin delayed Trump’s meeting by showing in late, so they had a two-hour private meeting (with only translators present) before having a briefer meeting with advisers. Putin reiterated his denial of Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election at the press conference that followed. Then, Trump shocked the world when he replied to a reporter’s query by saying that he trusted Putin’s denial more than the findings of his own intelligence agencies, which had led to the U.S. only a few days before.

12 Russian intelligence agents have been indicted by the Department of Justice for interfering with the election. Furthermore, when given the chance to denounce egregious Russian behavior, Trump chose to place the responsibility for the United States’ tense relationship with Russia. Trump also accepted Putin’s proposal to let American investigators access to Russian spies in exchange for access to Americans who are targets of Russian probes.

When questioned about whether he had supported Trump during the election by an American reporter, Putin said that he did, citing Trump’s stated desire for improved ties with Russia. Putin claimed that it would be impossible to gather compromising information on each of the more than 500 “high-ranking, high-level” American businessmen who were rumored to have attended the St. Petersburg Economic Forum when asked whether Russia had kompromat (compromiting information) on Trump. He then pointed to the conference.

Additionally, he said that during a prior trip, he was not aware of Trump’s attendance in Moscow. Nevertheless, some press versions of his response noted that Putin did not specifically deny possessing Trump-related kompromat. The conference was heralded in the Russian media as a tremendous victory for Putin. The summit’s outcome, according to Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, was “better than super.” The majority of the reactions in the US were ones of shock, and some Republicans joined Democrats in harshly criticizing Trump’s performance.

Constitutional change and the poisoning of Navalny

Putin’s standing was unaffected even though Russia continued to be a pariah on the international stage—its athletes were banned from international competition because of a significant state-sponsored doping program, the G8 suspended Russia indefinitely, and it was the subject of a number of economic sanctions. Putin faced a West that appeared to be lost, with Britain struggling to reach an agreement with the EU regarding its exit, German Chancellor Angela Merkel nearing the end of her time as the de facto leader of Europe, and governments in Poland and Hungary adopting more authoritarian policies.

In light of this, he bragged about a significant increase in Russian military might, particularly in the area of hypersonic weaponry. In December 2019, Putin said of the legendary arms race between the US and the USSR, “Today, we have a situation that is unique in modern history: they’re trying to catch up to us.”

Putin stated in January 2020 that he intended to change the Russian Constitution to eliminate presidential term limits, which would allow him to serve as president permanently. As soon as possible, Medvedev announced his resignation as prime minister, saying that a new administration would provide Putin “the opportunity to make the decisions he needs to make.” The proposed constitutional amendments were swiftly passed by the Russian legislature, but Putin nevertheless decided to hold a national vote, which some criticized as little more than political theater.

. The COVID-19 pandemic caused the original April date for that vote to be moved to July. Unsurprisingly, the outcome was a resounding endorsement of Putin’s agenda, but opposition parties pointed out that there was no impartial election monitoring.

Testing revealed that Navalny had been exposed to a novichok when he became extremely unwell on a flight from the Siberian city of Tomsk on August 20. After being taken to Germany to heal, Navalny unexpectedly fared well in the municipal elections that were held in the region where he had been campaigning the previous month. The Kremlin claimed any participation in the poisoning, but these denials lacked credibility because Navalny’s attack was simply the most recent in a string of attacks on the life of Putin’s detractors.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine

Putin commanded a significant Russian military buildup along the Ukrainian border in late 2021. Additional Russian units were also sent to Belarus, reportedly to participate in joint military drills with the Belarusian military. Concerns about what seemed to be an impending Russian invasion were expressed by Western nations, but Putin denied having such preparations. Up to 190,000 Russian soldiers were ready to invade Ukraine by February 2022 from forward bases in Russia, the Crimean Peninsula under Russian control, Belarus, and the separatist region of Transdniestria in Moldova, which was supported by Russia.

Additionally, under the pretense of previously scheduled naval drills, amphibious battalions were sent to the Black Sea. Putin effectively nullified the 2015 Minsk peace accord on February 21 when he acknowledged the independence of the self-declared people’s republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. On February 24, early in the morning, Putin declared the start of a “special military operation,” and explosions could be heard throughout Ukraine’s cities. Volodymyr Zelensky, the president of Ukraine, declared that his nation would defend itself. Western leaders denounced the unjustified strike and vowed to impose swift and punitive penalties against Russia.

The assumption made by Putin and his military advisors was that the Russian invasion of Ukraine would end in a matter of days with the overthrow of the democratically elected government in Kyiv and the establishment of a pro-Moscow regime. However, the Russian military’s shortcomings were immediately obvious, and in the face of tenacious Ukrainian resistance, advances along many axes stagnated. The attack on Kyiv was impeded by massive logistical problems, and despite Kharkiv’s proximity to the Russian border (20 miles [32 km]), an attempt to encircle it failed.

. Russian troops were forced out of Kyiv by the end of March, while the Russian Black Sea Fleet’s flagship missile cruiser Moskva was sunk by Ukrainian forces the following month.

There was abundant proof of war crimes committed by Russian soldiers in the freed territories. Numerous reports of sexual assault and looting were made, and dead of hundreds of citizens were discovered stacked in mass graves in cities including Bucha, Izyum, and Kherson. Up to 600 people were murdered in Mariupol after a Russian air attack hit a theater that was functioning as the major bomb shelter for the city.

The structure had no military significance, and the outside pavement was painted with the phrase “CHILDREN” in large Cyrillic characters that could be seen on satellite images. In flagrant violation of the Geneva Conventions, Russian commanders increased their attacks on civilian infrastructure as fighting triumphs more elusive and Ukraine started regaining territory. Mariupol had been reduced to a burning ruin when Russian troops eventually took the harbor city after a three-month siege.

Putin’s attempt to split the West and regain Russian influence in the nations that made up the former Soviet Union’s “near abroad” went horribly wrong. The fall of the pro-Russian Yanukovych administration in 2014 began a narrative arc that was eventually concluded on June 23, when the European Union officially gave Ukraine candidate status.

The obvious threat to the security of all of Europe galvanized NATO, and on July 5, two nations with a long tradition of neutrality—Finland and Sweden—signed agreements to join the alliance. Poland, which has a troubled history with its neighbor to the east, accepted millions of Ukrainian refugees. Western officials visited Kyiv to show their sustained support for Zelensky and Ukraine, and the United States handed Ukraine billions of dollars in military supplies. Putin, on the other hand, had a growing sense of isolation as Russia became the nation with the most economic sanctions in history.

Putin changed military leaders as his war effort faltered and eventually hired Yevgeny Prigozhin and his mercenary group, the Wagner Group, to handle some of the combat. Prigozhin recruited prisoners from Russian jails to swell Wagner’s ranks, and soon Prigozhin’s convict army was launching bloody assaults in the Donbas. On September 21, Putin announced a “partial mobilization” of 300,000 troops in response to the shocking losses incurred by Ukrainian counteroffensives. Despite assurances from defense authorities that only combat veterans would be called up, there was ample proof that males without prior military experience were being drafted. Thousands of men of military age fled the country as protests broke out all throughout Russia.

Some of these conscripts were killed in combat two weeks after getting their draft notices despite having inadequate equipment and receiving little training. The partial mobilization was opposed by even Putin’s most ardent allies in state media, but doing so came with a very real risk. Putin had enacted legislation that made criticizing the war effort a criminal punishable by up to 15 years in prison, and officials and oligarchs who irked Putin frequently died mysterious deaths, with a surprisingly high proportion falling from windows. Russia’s standing in the world had significantly decreased after a year of conflict, its economy was suffering due to sanctions, and its leader appeared more vulnerable than at any other point in his nearly 25-year rule.

Putin’s mobilization had little impact on the military environment in Ukraine, and Russia’s offensives in the winter and spring were ineffective. In an endeavor to secure some sort of triumph for the Kremlin, Wagner forces narrowed in on the city of Bakhmut. Poorly equipped Wagner prisoner troops tried to encircle Ukrainian forces for months while conducting brutal human wave attacks, but Ukrainian positions prevailed. The Ukrainians left the remains of Bakhmut in May 2023, and Prigozhin declared victory. It was believed that more than 100,000 Russians lost their lives in the conflict, with more than 20,000 of them being killed directly in combat. Nevertheless, it was Russia’s first victory on the battlefield in almost a year, and Prigozhin’s reputation improved as a result.

Late in June, when Prigozhin “declared war” on the Russian defense ministry and crossed back into Russia at the head of an armored column made up of about 25,000 Wagner mercenaries, internal strife between Prigozhin and the Russian military establishment reached a dramatic climax. On June 24, the Wagner force shot down over a dozen Russian aircraft before taking over the Rostov-on-Don headquarters of the Southern Military District.

After passing through Voronezh without encountering any significant resistance, Prigozhin’s column turned north and stopped just 120 miles (approximately 200 kilometers) south of Moscow. The Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko then quickly stated that he had mediated an agreement between Prigozhin and the Kremlin before Prigozhin immediately ordered his forces to return to their posts in Ukraine. The mercenaries would receive amnesty and military contracts in exchange for Wagner putting an end to their rebellion; Prigozhin would live in exile in Belarus.

Since his presidential jet was traced departing Moscow while Prigozhin was still on the move, it was unclear where Putin was during the uprising. Putin was allegedly “working at the Kremlin,” but it is undeniable that he maintained a surprisingly low profile on one of the most turbulent days in recent Russian history. When his public pronouncements did materialize, they came seen as frantic and contradictory.

He called Prigozhin a traitor and demanded that he be arrested, but Putin’s security forces took no action right away. Despite the fact that the mercenaries had killed numerous Russian servicemen during their assault on Moscow, Putin praised the Wagner warriors as heroes. Putin also praised the Russian army for averting “a civil war,” despite the fact that the Russian regular military appeared to be completely unprepared to put an end to the uprising.

Vladimir Putin Personal life

Family

Putin married Lyudmila Shkrebneva on July 28, 1983, and the two cohabitated in East Germany from 1985 until 1990. They have two daughters: Yekaterina Putina was born in Dresden, East Germany, on August 31, 1986, and Mariya Putina was born on April 28, 1985, in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg).

According to a Proekt investigation that was published in November 2020, Elizaveta, also known as Luiza Rozova, (born in March 2003), is Putin’s second child with Svetlana Krivonogikh. The Moskovsky Korrespondent reported in April 2008 that Putin had divorced Lyudmila and was engaged to Olympic gold medalist and politician Alina Kabaeva of Russia. The report was refuted, and the newspaper was soon shut down.[3] As a married couple, Putin and Lyudmila continued to make public appearances, although rumors began to circulate about the nature of his connection with Kabaeva.

Putin and Lyudmila declared their separation on June 6, 2013, and the Kremlin said it had been finalized on April 1, 2014. In 2015, Kabaeva allegedly gave birth to a daughter with Putin; this claim was later refuted. According to reports, Kabaeva and Putin had twin sons in 2019. However, Swiss media reported in 2022 that Kabaeva delivered a boy on both occasions, citing the couple’s Swiss gynecologist.

Through Maria, Putin has two grandsons who were born in 2012 and 2017. He supposedly also has a granddaughter through Katerina, who was born in 2017. Igor Putin, his cousin, was a director at the Master Bank in Moscow and was implicated in several money-laundering crimes.

Wealth

Putin’s fortune is estimated to be over 3.7 million rubles (US$280,000) in bank accounts, a private 77.4-square-meter (833 sq ft) apartment in Saint Petersburg, and various other assets, according to official data that was made public during the 2007 legislative election. Putin reportedly earned 2 million rubles ($152,000) in total in 2006. Putin listed 3.6 million rubles ($270,000) in income for 2012. Putin has been seen wearing several pricey wristwatches that are worth a combined $700,000, or about six times his yearly income. In the past, Putin has been known to offer gifts of watches for thousands of dollars. In 2009, he gave a Blancpain watch to a Siberian youngster he met while on vacation and another comparable watch to a factory worker the same year.

According to opposition politicians and journalists in Russia, Putin covertly owns a fortune worth several billions of dollars through his ownership of consecutive shares in a number of Russian businesses. Putin might not technically own these 43 planes, but as the only political force in Russia, he can act as though he does, according to a Washington Post editorial. The claim that “[Western] intelligence agencies… could not find anything” was made by an RIA Novosti correspondent. Polygraph.info examined a number of reports by Western (Anders Slund estimate of $100-160 billion) and Russian (Stanislav Belkovsky estimate of $40 billion), as well as counterarguments from Russian media, to analyze these contradictory claims. The polygraph revealed:

The exact amount of Putin’s wealth is unknown, and the Director of U.S. National Intelligence’s evaluation appears to be incomplete. However, Polygraph.info believes that Danilov’s assertion that Western intelligence agencies have not been able to find evidence of Putin’s riches is false given the mountain of information and papers in the Panama Papers and in the hands of independent investigators like those referenced by Dawisha.

11 million papers from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca were released in April 2016 to the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the German publication Süddeutsche Zeitung. Putin’s name did not appear in any of the records, and he denied having any connection to the business. However, three of Putin’s cronies on the list have been covered by various media outlets. Putin’s close friends and closest colleagues reportedly possess offshore businesses worth a total of $2 billion, according to the Panama Papers leak. The German publication Süddeutsche Zeitung finds it possible that Putin’s family may make money off of this money.

The US State Department had previously identified Bank Rossiya as being used by Putin as his personal bank account, and it was said in the paper that the US $2 billion had been “secretly shuffled through banks and shadow companies linked to Putin’s associates” like construction billionaires Arkady and Boris Rotenberg. Bank Rossiya played a key role in making this possible. “Putin has shown he is willing to take aggressive steps to maintain secrecy and protect [such] communal assets,” the report’s conclusion reads.

The majority of the money trail points to Sergei Roldugin, Putin’s closest pal. Although he describes himself as a musician and not a businessman, it appears he has collected assets worth at least $100 million. It has been asserted that his low profile led to his selection for the position. There have been rumors that Putin actually owns the funds and that Roldugin only served as a stand-in. Putin “controls enough money, probably more than any other person in the history of the human race,” according to Garry Kasparov.

Residences

Official government residences

In his roles as president and prime minister, Putin has occupied a number of government homes across the nation. The Moscow Kremlin, Novo-Ogaryovo in Moscow Oblast, Gorki-9 [ru] close to Moscow, Bocharov Ruchey in Sochi, Dolgiye Borody (home) in Novgorod Oblast, and Riviera in Sochi are some of these residences. Nine of the 20 mansions and palaces reported as belonging to Putin in August 2012 were constructed during his twelve years in power.

Personal residences

Putin constructed a dacha in Solovyovka on the eastern coast of Lake Komsomolskoye on the Karelian Isthmus in Priozersky District of Leningrad Oblast, close to St. Petersburg, not long after he returned from his KGB duty in Dresden, East Germany. Putin rebuilt the dacha after it burned down in 1996, and he was assisted by a group of seven pals who also constructed dachas nearby. The members officially established its fraternity as a cooperative organization in 1996, renaming it Ozero (“Lake”) and transforming it into a gated neighborhood.

Near the Black Sea town of Praskoveevka, a large Italianate-style mansion dubbed “Putin’s Palace” that is reportedly costing US$1 billion is being built. Former business colleague of Putin’s Sergei Kolesnikov claimed in 2012 that Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin had given him the go-ahead to supervise the palace’s construction on the BBC’s Newsnight program. Additionally, he said that the home, which was constructed on public property, had been erected for Putin’s personal use. It was outfitted with three helipads, a private driveway, and other amenities, all of which were paid for with public money and were under official Kremlin guard service security.

On January 19, 2021, Alexei Navalny and the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) released a video investigation accusing Putin of using fraudulently obtained funds to build the estate for himself in what they called “the world’s biggest bribe.” This was two days after Alexei Navalny was detained by Russian authorities upon his return to Russia. According to Navalny, who conducted the study, the estate is 39 times larger than Monaco and cost more than 100 billion rubles ($1.35 billion) to build.

Additionally, it displayed drone footage of the estate and a full blueprint of the palace, which Navalny claimed was provided by a contractor and which he compared to pictures of the palace’s interior that were posted online in 2011. Additionally, he described a complex corruption plan that allegedly involved members of Putin’s inner circle and allowed Putin to conceal billions of dollars needed to construct the estate.

Putin prefers to take an armored train rather a plane as a result of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Vladimir Putin Pets

Various world leaders have given Putin five dogs: Konni, Buffy, Yume, Verni, and Pasha. 2014 saw Konni’s passing. Tosya and Rodeo were the family’s two poodles when Putin first took office. After their divorce, they allegedly resided with his ex-wife Lyudmila.

Vladimir Putin Religion

Putin is an Orthodox Russian. While his father was an atheist, his mother was a devout Christian who visited a Russian Orthodox church. Despite the government’s persecution of her religion at the time, his mother frequently visited church even though she didn’t keep any icons at home. When he was a little child, his mother discreetly had him baptized, and she frequently took him to church.

Putin claims that after his wife was seriously injured in a car accident in 1993 and their dacha was destroyed by a life-threatening fire in August 1996, he experienced his first religious awakening. Putin’s mother gave him his baptismal cross just before an official trip to Israel, instructing him to have it blessed. Putin declares, “I followed her instructions and hung the cross around my neck. Since then, I have never taken it off.

In response to the question of whether he believes in God, he said in 2007: “There are things I believe, which in my position, at least, should not be shared with the public at large for everyone’s consumption because that would look like self-advertising or a political striptease.” Bishop Tikhon Shevkunov of the Russian Orthodox Church is said to be Putin’s confessor.[746] His old adviser Sergei Pugachev disregarded his genuineness in his Christian faith.

Vladimir Putin Sports

Putin follows FC Zenit Saint Petersburg and enjoys watching football. He also shows an interest in bandy and ice hockey, and on his 63rd birthday, he took part in a star-studded hockey game.

In September 2000, Putin was seen practicing judo in Tokyo, Japan.

Putin began training in judo when he was 11 years old and switched to sambo when he was 14 years old. In Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), he took first place in two sports. In 2012, he received the eighth dan of the black belt, making him the first Russian to do so. In 2014, he received an eighth-degree black belt in karate.

He co-wrote two books: Judo: History, Theory, Practice in English (2004) and Learn Judo with Vladimir Putin in Russian (2000). Putin’s martial arts prowess has been contested by Lawfare editor and black belt in taekwondo and aikido Benjamin Wittes, who claims that there is no video evidence of Putin showing any truly significant judo prowess.

Due to the Russian war in Ukraine, Putin was expelled from all posts within the International Judo Federation (IJF) in March 2022.

Vladimir Putin Health

William Burns, the director of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, said in July 2022 that there was no evidence to support the notion that Putin was unstable or unwell. The announcement was made in response to growing, unfounded media rumors regarding Putin’s health. Burns had previously served as the United States’ ambassador to Russia and has known Putin for more than 20 years, including during a private encounter in November 2021. Also denied as false by a Kremlin spokeswoman were reports about Putin’s poor health.

In 2018, the political publication Sobesednik [ru] in Russia claimed that Putin had a sensory chamber installed in his home in the Novgorod Oblast.

After spending two years in seclusion due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the White House, as well as Western generals, politicians, and political analysts, have questioned Putin’s mental health.

Based on video, the tabloid The Sun suggested that Putin might have Parkinson’s disease in April 2022. This rumor, which has not been confirmed by medical experts, has gained popularity in part as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which many people perceived as an insane action. Along with foreign medical experts who emphasize that it is impossible to identify the ailment based only on video recordings, the Kremlin denied the notion of Parkinson’s.

Did Putin serve in the military?

Before leaving his position as a KGB foreign intelligence officer in 1991 to start a political career in Saint Petersburg, Putin worked there for 16 years, attaining to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Where is Putin originally from?

In Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia), Putin was born on October 7, 1952.

How many presidents does Russia have?

Three people have held four presidential positions totaling six full terms. Vladimir Putin was elected as the country’s fourth president in May 2012; he was re-elected in March 2018 and took office in May for a six-year term. In 2024, he will be up for reelection.

How many man army does Russia have?

With 1.15 million active-duty members and at least two million reserve members, they are the fifth-largest military force in the world. By 2026, Russia intends to increase its active personnel force to 1.5 million, making it the third-largest in the world (after China and India).

How long can Putin be president?

Putin can avoid term limits in the elections of 2024 and 2030 thanks to a change made to the Constitution in 2020. This will allow him to continue serving in government until 2036.

Has an American president ever been to Russia?

Roosevelt to the Soviet Union in 1945 was a result of diplomatic exchanges between the Allies during World War II. Gerald Ford traveled to both the Soviet Union and Northern Asia for the first time as president in 1974 as a result of the Cold War détente between the two countries.

Discover more from Labaran Yau

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.