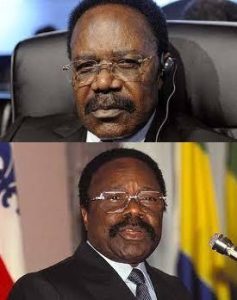

Former Gabon President Omar Bongo Biography

El Hadj Omar Bongo Ondimba was a Gabonese politician who served as the country’s second president for nearly 42 years, from 1967 to his passing in 2009. He was born Albert-Bernard Bongo and died on June 8, 2009. Before becoming the vice-president of Gabon in his own right in 1966, Bongo was elevated to important posts as a young official under the country’s first president, Léon M’ba, in the 1960s. After M’ba died in 1967, he succeeded him as the nation’s second president.

The Gabonese Democratic Party (PDG) was run by Bongo as a one-party system until 1990, when he was compelled to introduce multi-party politics in Gabon due to popular outcry. His political longevity, despite fierce opposition to his leadership in the early 1990s, appeared to be the result of him solidifying his hold on power by winning over the majority of the key opposition figures at the time. Despite the intense controversy surrounding the 1993 presidential election, he was re-elected that year and in the elections that followed in 1998 and 2005.

With each subsequent election, his separate parliamentary majorities grew and the opposition became more quiet. Following Fidel Castro’s resignation as president of Cuba in February 2008, Bongo assumed the title of longest-reigning non-royal leader in the world. Since 1900, he has one of the longest reigns of the non-royal kings.

In essence, Bongo was condemned for working for himself, his family, and local elites rather than for Gabon and its citizens. For instance, French environmentalist Eva Joly asserted that during Bongo’s lengthy rule, despite an oil-driven GDP per capita growth to one of the highest levels in Africa, Gabon only built 5 km of freeway a year and continued to have one of the highest infant mortality rates around when he passed away in 2009.

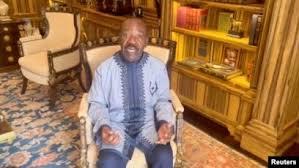

After Bongo passed away in June 2009, his son Ali Bongo was chosen to succeed him in August of that same year. Ali Bongo had long been given important ministerial duties by his father.

Omar Bongo Early life

The youngest of twelve children, Albert-Bernard Bongo was born on December 30, 1935, in Lewai, French Equatorial Africa, a village in the Haut-Ogooué province in what is now southeast Gabon, close to the Republic of the Congo border. Lewai has subsequently been renamed Bongoville. He belonged to the little Bateke ethnic group. El Hadj Omar Bongo became his new name after converting to Islam in 1973.

After completing his primary and secondary education in Brazzaville, the then-capital of French Equatorial Africa, Bongo worked for the Post and Telecommunications Public Services before enlisting in the French military. He served in the Air Force as a second lieutenant, first lieutenant, and captain in succession while stationed in Brazzaville, Bangui, and Fort Lamy (the current N’djamena, Chad).

Omar Bongo Education and music career

After attending an elite school in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, Bongo went on to the Sorbonne to study law. Wuhan University in China awarded him an honorary doctorate of law in 2018. He released A Brand New Man, a funk album in 1977, with Charles Bobbit as producer.

Omar Bongo Political career

Pre-Presidency

Albert-Bernard Bongo started his political career after Gabon gained independence in 1960, quickly moving up through a series of appointments under President Léon M’ba. In the 1961 parliamentary election in Haut Ogooué, Bongo supported M. Sandoungout while deciding not to stand for office himself. Sandoungout won the election and was appointed Minister of Health. After a brief stint at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bongo was appointed Assistant Director of the Presidential Cabinet in March 1962. Seven months later, he was promoted to Director. M’ba was abducted in 1964 during the lone coup attempt in 20th-century Gabon, and Bongo was imprisoned in a military barracks in Libreville. M’ba was later returned to power two days later.

He was designated as a Presidential Representative on September 24, 1965, and given responsibility for coordination and defense. The job of Minister of Information and Tourism was subsequently officially given to him in August 1966 after being appointed first on an interim basis. On November 12, 1966, M’ba, whose health was deteriorating, named Bongo as Vice-President of Gabon. M’ba was re-elected as president and Bongo was chosen as vice president in the same presidential election that was place on March 19, 1967. Since November 1966, when President Léon M’ba was suffering from a protracted illness, Bongo has effectively been in charge of Gabon.

Single-party rule

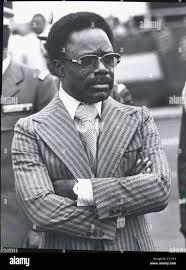

Following the passing of M’ba four days earlier on December 2nd, 1967, de Gaulle and other key French figures installed Bongo as President. At 32 years old, Bongo was Africa’s fourth-youngest president at the time, behind Togo’s sergeant Gnassingbé Eyadéma and Burundi’s captain Michel Micombero. The Gabonese Independence Party, formerly known as the Bloc Democratique Gabonais (BDG), was renamed the Parti Democratique Gabonais (PDG) in March 1968 after Bongo declared Gabon to be a one-party state.

Bongo was the only contender for president in the 1973 elections for the national legislature and the presidency. 99.56% of the total votes cast were in favor of him and the other PDG candidates. In order to make Léon Mébiame, who had served as vice president alongside Bongo’s presidency since 1967, prime minister, Bongo abolished the role of vice president in April 1975. Mebiame would hold the position of prime minister until 1990, when he would step down.

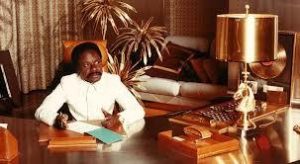

In addition to serving as president from 1967 through 1975, Bongo also served as minister of defense from 1967 to 1981, information from 1967 to 1980, planning from 1967 to 1977, prime minister from 1967 to 1975, and interior from 1967 to 1970, among many other positions. Following the PDG Congress in January 1979 and the elections in December 1979, Bongo relinquished some of his ministerial responsibilities and handed over leadership of the government to Prime Minister Mebiame. The PDG congress had called for a halt to the holding of numerous offices and condemned Bongo’s administration for its inefficiency. In 1979, Bongo was re-elected with 99.96% of the vote for another seven-year term.

As Gabonese economic hardships grew increasingly severe in the late 1970s, opposition to President Bongo’s administration initially emerged. The Movement for National Restoration (Mouvement de redressement national, MORENA) was the first organized but unregistered opposition group. In December 1981, during the university’s brief closure, this moderate opposition organisation funded protests by students and faculty members at the Université Omar Bongo in Libreville.

MORENA requested the restoration of a multi-party democracy and accused Bongo of being corrupt, engaging in excessive personal spending, and favoring his own Bateke tribe. When the opposition handed out flyers condemning the Bongo government during the visit of Pope John Paul II in February 1982, arrests were made. 37 MORENA members were prosecuted and found guilty of crimes against state security in November 1982. All of the accused received severe punishments, including 20 years of hard labor for 13 of them, but by mid-1986, they had all been pardoned and released.

Omar Bongo remained committed to one-party control in the face of these pressures. A single list of candidates was subsequently presented once PDG had authorized all nominations for the parliamentary elections that were held in 1985. On March 3, 1985, the nominees were approved by the general public. Bongo was re-elected in November 1986 with 99.97% of the vote.

Multi-party rule

The PDG central committee and the National Assembly approved constitutional modifications to speed up the transition to a multi-party system on May 22, 1990, following strikes, riots, and other turmoil. The preexisting presidential mandate, which was in existence until 1994, was to be upheld. The presidential term of office was changed to five years with a term limit of one re-election, and subsequent presidential elections would feature more than one contender.

The following day, on May 23, 1990, Joseph Rendjambe, an outspoken opponent of Bongo and the head of the political opposition, was discovered dead in a hotel, having supposedly been poisoned. The worst riots under Bongo’s 23-year rule began with the killing of Rendjambe, a well-known business executive and secretary-general of the opposition party Parti gabonais du progres (PGP). The French consul general as well as ten workers from an oil business were held hostage, and presidential buildings in Libreville were set on fire. In Port Gentil, the hometown of Rendjambe and an important oil production location, French troops evacuated foreigners and a state of emergency was proclaimed.

The two largest oil producers in Gabon, Elf and Shell, reduced production from 270,000 barrels per day (43,000 m3/d) to 20,000 during this emergency. If they didn’t return to regular output right away, Bongo threatened to revoke their exploration permits. Fortunately, they did. In order to “protect the interests of 20,000 resident French nationals,” France dispatched 500 troops to augment the 500-man battalion of Marines continuously stationed in Gabon. To stop riots, tanks and soldiers were stationed all around the presidential residence.

By a far smaller margin of 51.4% in December 1993, Bongo won the first presidential election held under the new multi-party constitution. Candidates in opposition declined to certify the election results. Following significant civil unrest, the administration and several opposition groups decided to cooperate in finding a political solution. These discussions resulted in the Paris Accords in November 1994, which included a number of opposition members in a government of national unity.

However, this arrangement quickly fell apart, and the legislative and municipal elections in 1996 and 1997 served as the catalyst for the return of party politics. Despite several significant cities, like Libreville, electing opposition mayors in 1997, the PDG nonetheless won the legislative election by a wide margin. Eventually, Bongo was able to successfully reestablish his hold on power, and by coaxing or buying off the majority of the key opposition figures, he was able to easily win re-election in 1998.

In 2003, Bongo succeeded in getting the Constitution amended to give him the right to run for office as many times as he wished and extend the presidential term from five to seven years. Critics of Bongo said that he intended to govern forever. On November 27, 2005, Bongo won a seven-year term as president with 79.2% of the vote, easily defeating his four rivals. On January 19, 2006[19], he was inaugurated for a second seven-year term. He served as president until his passing in 2009.

Relations with France

The little African nation of Gabon has long been influenced by French culture, politics, and economics. Since gaining independence in 1960, the colonial French rule has been replaced by an ominous reconciliation with Paris crafted by Gabon’s government. Gabon is an extreme case of neocolonialism that borders on caricature, according to a French journalist who has lived on the continent for a long time.

Given that Gabon was a member of Françafrique, Bongo’s relationships with France predominated his international affairs and those of Gabon as a whole. Gabon has always been significant to France because of its oil, which accounts for a fifth of the world’s known uranium (Gabonese uranium supplied France’s nuclear bombs, which President Charles de Gaulle tested in the Algerian deserts in 1960), large iron and manganese deposits, and an abundance of lumber. “Gabon without France is like a car without a driver,” allegedly claimed Bongo. Gabon without France is like a car without gas.

In 1964, when rebel soldiers kidnapped president M’ba and arrested him in Libreville, French paratroopers saved the president and Bongo and returned them to power. Following what was essentially an interview with de Gaulle in Paris in 1965 and his subsequent approval, Bongo was appointed Vice President in 1966.

The New York Times stated in 1988 that “French funding to Gabon totaled US$360 million last year. This includes paying for the salaries of 170 French advisers and 350 French teachers, as well as scholarships for the majority of the roughly 800 Gabonese students who study in France each year. Low-interest trade loans were also extended. [A]According to the French opposition monthly Le Canard enchaîné, US$2.6 million of this funding was also used to decorate President Bongo’s DC-8 jet’s interior.

In 1990, in the face of persistent pro-democracy rallies that threatened to topple Bongo, France, which has always kept a permanent military post in Gabon as well as in several of its other ex-colonies, assisted in keeping Bongo in power. After the country’s first multiparty presidential elections in 1993, when the opposition staged violent protests, Gabon was on the verge of civil war. Paris sponsored talks between Bongo and the opposition, which led to the Paris Agreement/Accords, which brought about peace.

Mr. Bongo and his family resided in the exclusive world of the super-rich in France, his longtime supporter. According to Transparency International, they had access to 39 opulent homes, 70 bank accounts, and at least 9 opulent cars, each valued about US$2 million….

According to Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Jacques Chirac’s candidacy for president in 1981 received funding from Bongo. Giscard claimed that over time, Bongo had created a “very dubious financial network.” “I contacted Bongo and told him, ‘You’re backing my rival’s campaign,’ and there was this astonishing dead stillness that I can still clearly recall before he answered, ‘Ah, you know about it. I stopped having personal relationships with him after that, said Giscard.

According to socialist legislator André Vallini, Bongo apparently contributed to numerous left- and right-wing electoral campaigns in France. President Nicolas Sarkozy removed Jean-Marie Bockel, the minister in charge of overseeing the former colonies, in 2008 after the latter had brought attention to the “squandering of public funds” by some African regimes, inciting Bongo’s wrath.

Political analyst Nicholas Shaxson, the author of a book on Africa’s oil states, claimed that he made his nation and its oil business available as a source of offshore slush funds. All of the French political parties, from the left to the right, used these for covert party funding and as a source of bribery to support French commercial ambitions around the world.

President Sarkozy declared his “sadness and emotion” following Bongo’s passing and vowed that France will continue to be “loyal to its long relationship of friendship” with Gabon. “It is a great and loyal friend of France who has left us — a grand figure of Africa,” Sarkozy said in a statement.

Allegations of corruption

Francesco Smalto, an Italian fashion designer, acknowledged giving Bongo access to Parisian prostitutes in exchange for a $600,000 annual tailoring contract.

One of the richest leaders of state in history, Bongo’s wealth was mostly the result of oil profits and allegations of corruption. The president of Gabon allegedly kept US$130 million in personal accounts at Citibank, according to a 1999 investigation by the US Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations into Citibank. The money, according to the Senate report, was “sourced in the public finances of Gabon.”

When the United States Senate Indian Affairs Committee looked into lobbyist Jack Abramoff’s questionable fundraising practices in 2005, they discovered that Abramoff had proposed to set up a meeting between Bongo and George W. Bush for $9,000,000. Bush and Bongo met in the Oval Office ten months after the alleged financial exchange, despite the fact that it has not been confirmed.

Inge Lynn Collins Bongo, his son Ali Bongo’s second wife and former daughter-in-law, made headlines in 2007 when she starred in the reality series Really Rich Real Estate on the US music channel VH1. She was shown attempting to purchase a $25 million property in Malibu, California.

Recent French criminal investigations into hundreds of millions of euros in shady payments made by Elf Aquitaine, the former French state-owned oil company, referenced Bongo. One Elf representative said that the corporation paid Bongo 50 million euros year to use the Gabonese oil reserves.

As of June 2007, Bongo, along with President Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of the Congo, Blaise Compaoré of Burkina Faso, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea and José Eduardo dos Santos from Angola was being investigated by the French magistrates after the complaint made by French NGOs Survie and Sherpa due to claims that he has used millions of pounds of embezzled public funds to acquire lavish properties in France. All of the leaders denied any misconduct.

On June 20, 2008, The Sunday Times (UK) published the following:

President Omar Bongo Ondimba of Gabon recently purchased a £15 million mansion in one of Paris’ most affluent neighborhoods. According to a French judicial investigation, Bongo, 72, and his family also purchased a fleet of limousines, including a £308,823 Maybach for Bongo’s wife, Edith, 44. Some of the cars’ purchase price was deducted right from Gabon’s treasury.

The Paris home is close to the Elysée Palace in the Rue de la Baume. The 21,528 square foot (2,000 square meters) residence was purchased by a Luxembourg-based real estate firm in June of last year. …the property is the most expensive in his portfolio, which also comprises nine other properties in Paris, four of which are on the prestigious Avenue Foch, close to the Arc de Triomphe. The firm’s partners include two of Bongo’s children, Omar, 13, and Yacine, 16, his wife Edith, and one of her nephews. In the same street, he also rents a nine-room apartment. In addition to these seven residences, Bongo also owns four villas in Nice, one of which includes a pool.

Edith owns a home in Nice as well as two apartments close to the Eiffel Tower. Through tax data, investigators were able to locate the properties. They were able to learn information about Bongo’s car fleet after performing checks at his residences. To purchase the Maybach, which was painted Côte d’Azur blue, in February 2004, Edith used a check drawn on an account in the name of “Prairie du Gabon en France” (a division of the Gabon treasury). Two years later, Pascaline Bongo, 52, used a check from the same account to pay a portion of £29,497 toward a £60,000 Mercedes.

For £153,000, Bongo purchased a Ferrari 612 Scaglietti F1, while his son Ali paid £160,000 for a Ferrari 456 M GT in June 2001. Bongo’s success has frequently been in the news. A 1997 US Senate investigation states that his family spends £55 million annually. An executive claimed that Elf Aquitaine paid Bongo £40 million annually via Swiss bank accounts in exchange for authorization to use his country’s reserves in a separate French investigation into corruption at the former oil major Elf Aquitaine.

Bongo disagreed. Following a lawsuit accusing Bongo and two other African leaders of embezzling public funds to pay for their purchases, the French antifraud agency OCRGDF launched its most recent investigation. No one can seriously accept that these properties were purchased with their wages, regardless of the merits and qualifications of these leaders, according to the complaint filed by the Sherpa group of judges, which promotes corporate social responsibility.

In 2009, Bongo’s final months were spent fighting with France over the French investigation. His bank accounts were frozen by a French court in February 2009, adding fuel to the fire. His administration accused France of pursuing a “campaign to destabilize” the nation. Because of this, he was hospitalized and passed away in Barcelona, Spain, rather than in France.

Leadership style

He dominated with a tidy mustache and a sharp gaze frequently masked behind dark spectacles. He was short, like many members of his marginalized Bateke ethnic group, and frequently donned high platform shoes to give the impression that he was taller. In spite of his short size, he was one of the last of the so-called “big men” on the African continent, and he ruled Gabon with smart acumen for nearly 42 years.

One of the last of the African “Big Man” dictators, Omar Bongo was known as Africa’s “little Big Man” and was described as “a diminutive, dapper figure who conversed in flawless French, a charismatic figure surrounded by a personality cult”. France, income from Gabon’s 2,500,000,000 barrels (400,000,000 m3) of oil reserves, and his political savvy served as the cornerstones of his lengthy rule.

As a fervent supporter of France, Bongo was pleased to negotiate a good deal with the former colonial power, France, when he first took office. He granted exclusive rights to French oil giant Elf Aquitaine to use Gabon’s oil riches in exchange for Paris ensuring his hold on power indefinitely.

After that, Bongo oversaw an oil boom that surely supported his and his family’s expensive lifestyle, which included dozens of opulent homes in and around France, a US$800 million presidential residence in Gabon, posh automobiles, etc. He was able to do this and eventually become one of the richest men in the world. In order to prevent widespread unrest, he carefully let just enough oil revenue to flow down to the general population of 1.4 million.

He established some basic infrastructure in Libreville and disregarded recommendations to build a road network in favor of building the US$4 billion Trans-Gabon Railway line that runs deep inside the interior forest. Petrodollars paid the wages of a bloated public service, distributing among the populace enough of the state’s riches to keep the majority of people clothed and fed. The UK publication Guardian portrayed Bongo’s Gabon in 2008.

Some sugar, beer, and bottled water are produced in Gabon. Despite the tropical heat and fertile soil, there is very little agricultural production. Trucks from Cameroon deliver fresh produce. French milk is flown in. Additionally, many Gabonese have no interest in looking for employment outside the public sector due to years of dependence on family who have civil service jobs; most manual tasks are filled by immigrants.

A portion of the funds were used by Bongo to create a sizable support network for him, including ministers, top officials, and military personnel. He had learned from M’ba how to assign various tribal groups government ministries so that each significant group had a representative in the government. Outside of self-interest, Bongo had no philosophy, and neither did the opposition. He held power through understanding how to exploit other people’s self-interest.

He had a talent for winning over opponents to his cause. He co-opted or bought off opponents rather than outright suppressing them by offering detractors minor portions of the country’s oil revenue. He was the most prosperous of all the Francophone African leaders, and he easily maintained his political power into the fifth decade.

The 1993 multi-party presidential elections, which he won, were clouded by charges of cheating, with the opposition alleging that his main competitor, Father Paul Mba Abessole, had been cheated out of the victory. Due to violent protests by the opposition, Gabon was on the verge of a civil war. Bongo stepped into negotiations with the opposition and negotiated what is now known as the Paris Agreement in an effort to demonstrate that he was not a dictator who relied on force to maintain his political power.

Similar controversy erupted when Bongo won the second presidential election held in 1998. In response, the president met with some of his detractors to propose amending the law to ensure free and fair elections. Following his party’s overwhelming victory in the 2001 parliamentary elections, Bongo offered key opposition figures positions in the cabinet. In the sake of “friendly democracy,” Father Abessole accepted a ministry position.

The prominent opposition figure, Pierre Mamboundou of the Gabonese People’s Union, declined to go to the gatherings after the 1998 elections, believing that Bongo was only using them as a ruse to entice the opposition figures. The ballot boxes and papers from a polling place in Mamboundou’s hometown of Ndende were set ablaze by his supporters after he called for a boycott of the legislative elections that were held in December 2001. After the 2001 legislative elections, he later turned down offers for a high position. Bongo threatened to have Mamboundou arrested, but this never happened. The president claimed that his “best retaliation” was a “policy of forgiveness.”

Maboundou, however, stopped publicly criticizing Mr. Bongo in 2006. The former brand was open about the president’s promise to donate him $21.5 million for the growth of his Ndende constituency. Bongo became more and more reliant on his own family as time went on. In 2009, his daughter Pascaline served as the head of the president’s administration, while her husband, Paul Toungui, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, had been his son Ali by his first marriage since 1999.

He put an end to a student walkout in 2000 by paying roughly $1.35 million to buy the computers and books they had been demanding. “He was a self-described nature enthusiast in a nation that has the most unexplored virgin jungle of any country in the Congo Basin. He declared 10% of Gabon’s land to be national parks in 2002, promising that they would never be mined, logged, hunted, or farmed. He wasn’t above a little self-promotion, so Gabon got Bongo University, Bongo Airport, a lot of Bongo Hospitals, Bongo Stadium, and Bongo Gym. Unavoidably, Lewai, the president’s hometown, was changed to Bongoville.

In an effort to resolve the conflicts in the Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Burundi, and Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bongo developed a reputation as a mediator on the global stage.[46] When Bongo won the Dag Hammarskjöld Peace Prize in 1986 for his efforts to end the Chad-Libya border war, his reputation outside was improved. Because he had ensured peace and stability during his reign, he was well-liked by his own people.

A unusual accomplishment for a country surrounded by unstable, war-torn states, Gabon never had a coup or civil conflict while Mr. Bongo was in power. Oil-based, the nation’s economy resembled more that of an Arabian emirate than that of a Central African country. For many years, Gabon was rumored to have the highest per capita consumption of Champagne in the world—possibly apocryphally.

Despite the significant oil revenues, the political scientist Thomas Atenga claims that “the Gabonese rentier state has functioned for years on the predation of resources for the benefit of its ruling class, around which a parasitic capitalism has developed, barely improving the living conditions of the population.”

Omar Bongo Personal life

While on a trip to Libya in 1973, Bongo embraced Islam and adopted the name Omar. Muslims were at the time a very small portion of the native population; after Bongo’s conversion, their numbers increased but they still made up a very small portion of the population. On 15 November 2003, he changed his last name to Ondimba in honor of his father, Basile Ondimba, who passed away in 1942.

Louise Mouyabi-Moukala was the bride of Bongo’s first marriage. In 1957, their daughter Pascaline was born in Franceville. Foreign Minister of Gabon Pascaline later served as Director of the Presidential Cabinet.

Marie Josephine Kama, afterwards known as Josephine Bongo, was the bride in Bongo’s second marriage. She launched a music career under the name Patience Dabany after he divorced her in 1987. Alain Bernard Bongo, a boy, and Albertine Amissa Bongo, a daughter, were born to them. Alain Bernard Bongo (after known as Ali-Ben Bongo), who was born in Brazzaville in 1959, held the positions of foreign minister from 1989 to 1992 and defense minister from 1999 to 2009 before being elected president in August 2009 to succeed his father.

Then, in 1989, Bongo wed Edith Lucie Sassou-Nguesso, who was over 30 years his junior. She was the child of the president of the Congo, Denis Sassou-Nguesso. She had pediatrician training and was well-known for her dedication to the AIDS epidemic. She had two children with Bongo. Four days after turning 45, Edith Lucie Bongo passed away in Rabat, Morocco, where she had been receiving treatment for several months, on March 14, 2009. Her cause of death and the nature of her sickness were not disclosed in the statement announcing her passing. Prior to her passing, she had not made an appearance in public for about three years. On March 22, 2009, she was laid to rest in her home Congo in the family cemetery of the northern town of Edou.

Over 30 children were born to Bongo’s wives and other partners in total.

Bongo did have a small amount of scandal. The New York Times stated in 2004 that

Peru is looking into allegations that a candidate in a beauty competition was persuaded to go to Gabon in order to fall in love with the country’s 67-year-old president, Omar Bongo, and was left stranded for almost two weeks when she refused. According to Mr. Bongo’s spokesperson, he was not aware of the accusations. Ivette Santa Maria, a 22-year-old contender for Miss Peru America, was reportedly invited to Gabon to conduct a pageant there, according to the Peruvian Foreign Ministry.

Ms. Santa Maria claimed in an interview that she was driven to Mr. Bongo’s presidential mansion shortly after arriving on January 19 and that as he joined her, he touched a device that caused some sliding doors to open to expose a big bed.

She claimed that she informed the man that she was Miss Peru and not a prostitute. Guards offered to bring her to a motel after she ran away. She was stranded in Gabon for 12 days without the means to pay the fee, though, before international women’s organizations and others stepped in.

Omar Bongo Family

Sylvia Valentin, a French native who was born to Édouard Valentin, the CEO of the Omnium Gabonais d’Assurances et de Réassurances (OGAR), was Ali Bongo’s first wife. They wed in 1989. At the Gabonese Employers Confederation (Confédération patronale gabonaise, CPG), Édouard Valentin is the Chargé des affaires sociales, while his wife Evelyne works in the presidency’s office.

Ali Bongo wed his second wife, American Inge Lynn Collins Bongo, a native of Los Angeles, in 1994. Inge Bongo was a recipient of food stamps when Ali Bongo was elected president in California, and she filed for divorce in 2015.

He and Sylvia adopted four children in 2002: Malika Bongo Ondimba, a daughter, Noureddin Bongo Valentin (in French), Jalil Bongo Ondimba, and Bilal Bongo.

Omar Bongo Illness and death

The Gabonese government revealed on May 7th, 2009, that Bongo had taken time off from his official responsibilities to grieve over his wife and rest in Spain.

However, it was revealed by the international media that he was gravely ill and receiving cancer treatment in a hospital in Barcelona, Spain. The Gabonese administration initially insisted that he was in Spain for a few days of rest after experiencing “intense emotional shock” after the loss of his wife, but later acknowledged that he was actually “undergoing a medical check up” in a Spanish clinic.

Unconfirmed rumors claiming to be from French media and sources “close to the French government” said that Bongo had passed away in Spain from complications from severe cancer on June 7, 2009. The reports, which had been covered by various other news outlets, were refuted by the government of Gabon, who continued to maintain his health. Finally, the Gabonese Prime Minister Jean Eyeghe Ndong announced in a written statement that Bongo had passed away on June 8, 2009, just before 12:30 GMT, from a heart attack.

Thousands of people came to pay their respects as Bongo’s body was flown back to Gabon and laid in state for five days. A state funeral was held on June 16, 2009, in Libreville. Nearly two dozen African heads of state, including several who had ruled the continent for decades, as well as the only Western heads of state in attendance—French President Nicolas Sarkozy and his predecessor Jacques Chirac—attended.

Then, Bongo’s remains was transported by air to Franceville, the largest city in the southeasterly province of Haut-Ogooue, where he was born. On June 18, 2009, a private family funeral took place there for Bongo.

Omar Bongo Net Worth

Omar Bongo, the former president of Gabon, maintained a secretive approach when revealing his net worth, leaving it unknown to the public. Nevertheless, it is widely recognized that he was among the wealthiest leaders worldwide.

The primary source of his considerable wealth was predominantly linked to revenue generated from the oil industry and his alleged involvement in corrupt practices. Despite the absence of concrete figures, there is no denying that Omar Bongo possessed immense financial resources during his tenure as head of state.

According to research, Omar Bongo would have accumulated an estimated net worth of $1 billion before passing on.

What did Omar Bongo do?

Former French air force commander and politician Omar Bongo Ondimba assumed control in the years following independence and ruled Gabon for 42 years before passing away in 2009.

How long did Omar Bongo rule Gabon?

Omar Bongo, the 42-year-old leader of Gabon, passed away in 2009. The nation observed a month of mourning and 15 foreign leaders, including the president of France, attended his weeklong state funeral.

Discover more from Labaran Yau

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.