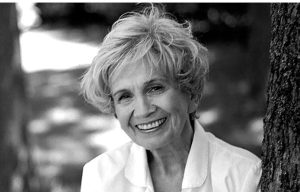

Alice Munro Biography

Alice Ann Munro (/mənˈroʊ/; née Laidlaw /ˈleɪdlɔː/; 10 July 1931 – 13 May 2024) was a Canadian short story writer who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013.

Munro’s work has been described as altering the architecture of the short story, particularly its inclination to go forward and backward in time, as well as its use of integrated short fiction cycles.

Her stories appear to drown rather than declare, and to tell rather than parade. She was dubbed the “master of the short story.”

Munro’s writing is frequently set in her native Huron County, southwestern Ontario.

Her stories examine human intricacies in straightforward prose.

Her writing earned her the reputation of being a remarkable writer in the same vein as Chekhov.

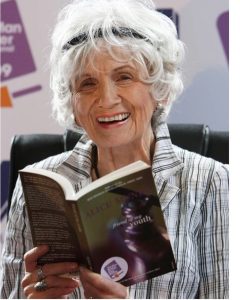

Aside from the Nobel Prize, Munro garnered other prizes for her work as “master of the contemporary short story,” including the 2009 Man Booker International Prize for her whole body of work.

She also won Canada’s Governor General’s Award for Fiction three times, the Writers’ Trust of Canada’s Marian Engel Award in 1996, and the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize in 2004 for her work Runaway.

Alice Munro Profile | |

| Born | Alice Ann Laidlaw 10 July 1931 Wingham, Ontario, Canada |

|---|---|

| Died | 13 May 2024 (aged 92) Port Hope, Ontario, Canada |

| Occupation | Short-story writer |

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | The University of Western Ontario |

| Genre | Short fiction, short story cycle, literary fiction |

| Notable awards | Governor General’s Award (1968, 1978, 1986) Giller Prize (1998, 2004) Man Booker International Prize (2009) Nobel Prize in Literature (2013) |

| Spouse | James Munro (m. 1951; div. 1972) Gerald Fremlin (m. 1976; died 2013) |

| Children | 4 |

Alice Munro’s Early Life and Education

Munro was born Alice Ann Laidlaw in Wingham, Ontario. Her father, Robert Eric Laidlaw, was a fox and mink farmer who subsequently transitioned to turkey farming.

Her mother, Anne Clarke Laidlaw (née Chamney), was a teacher.

She was of Irish and Scottish origin, and her father was a descendent of Scottish poet James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd.

Munro began writing as a youngster and published her first story, “The Dimensions of a Shadow,” in 1950 while studying English and journalism at the University of Western Ontario on a two-year scholarship.

She worked as a waitress, tobacco picker, and library clerk during this time.

In 1951, she left the university, where she had been studying English since 1949, to marry fellow student James Munro.

They relocated to Dundarave, West Vancouver, for James’ job at a department store. In 1963, the pair moved to Victoria, where they started Munro’s Books, which is still operational.

Alice Munro Career

Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), Munro’s highly regarded first collection of tales, won the Governor General’s Award, Canada’s highest literary prize at the time.

This achievement was followed by Lives of Girls and Women (1971), a compilation of interconnected stories.

Munro’s collection of interlinked stories, Who Do You Think You Are?, was published in 1978.

This work received Munro a second Governor General’s Literary Award and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1980 under the worldwide title The Beggar Maid.

Munro made public appearances and gave readings in Australia, China, and Scandinavia between 1979 and 1982.

In 1980, she held the role of writer in residence at the University of British Columbia and the University of Queensland.

From the 1980s to 2012, Munro published a collection of short stories every four years.

Munro’s stories were first published in periodicals such as The Atlantic Monthly, Grand Street, Harper’s Magazine, Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, Narrative Magazine, and The Paris Review.

Her collections have been translated into thirteen languages.

Munro received the Nobel Prize in Literature on October 10, 2013, and was described as a “master of the contemporary short story”. She was the first Canadian and the 13th woman to earn the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Munro is well-known for her lengthy collaboration with editor and publisher Douglas Gibson.

When Gibson left Macmillan of Canada in 1986 to start the Douglas Gibson Books label at McClelland and Stewart, Munro returned the advance Macmillan had previously paid her for The Progress of Love, allowing her to join Gibson at the new company.

Munro and Gibson maintained their professional relationship; when Gibson released his memoirs in 2011, Munro penned the introduction, and until her death, Gibson frequently made public appearances on Munro’s behalf when her health prevented her from attending in person.

Almost 20 of Munro’s works have been made available for free on the Internet, however, most are merely the earliest copies.

Before 2003, Munro’s compilations featured 16 stories more than twice, with two of her works receiving four republications: “Carried Away” and “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage”.

Munro’s short stories have been adapted into films such as Martha, Ruth, and Edie (1988), Edge of Madness (2002), Away from Her (2006), Hateship, Loveship (2013), and Julieta (2016).

Several of Munro’s stories are set in Huron County, Ontario.

One of the defining characteristics of her fiction is its strong regional focus. After winning the Nobel Prize, she was asked, “What could be so interesting about describing small-town Canadian life?” Munro said, “You just have to be there.”

Another aspect is an omniscient narrator who helps us make sense of the world. Many people liken Munro’s small-town settings to writers from the rural American South.

Munro’s characters, like those of William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, frequently encounter deeply ingrained customs and traditions, although their reactions are generally more measured than those of their Southern counterparts.

Her male characters seem to embody the spirit of the common man, but her feminine characters are more sophisticated. Much of Munro’s work represents the Southern Ontario Gothic literary type.

Munro’s work is frequently compared to the great short-story authors. In her works, as in Chekhov’s, the storyline is secondary, and little happens.

Garan Holcombe, like Chekhov, writes: “All is based on the epiphanic moment, the sudden enlightenment, the concise, subtle, revelatory detail.”

Munro’s work explores “love and work, and the failings of both.” She shares Chekhov’s fascination with time and our lamentable inability to slow or stop its continuous march onward.”

The challenges of a girl coming of age and coming to grips with her family and her small community have been recurring themes in her work, notably in her early stories.

In Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage (2001) and Runaway (2004), she changed her focus to the struggles of middle-aged women, the elderly, and single women.

Her characters frequently have a discovery that sheds light on and offers significance to a situation.

Her stories examine human intricacies in straightforward prose.

The style of Munro displays the inconsistencies of “ironic and serious at the same time,” “mottoes of godliness and honor and flaming bigotry,” “special, useless knowledge,” “tones of shrill and happy outrage,” “the bad taste, the heartlessness, the joy of it.”

Her work juxtaposes the spectacular and the mundane, with each undercutting the other in ways that simply and naturally depict life. Robert Thacker writes:

Munro’s work fosters empathy among readers, particularly critics. We are pulled to her writing by its verisimilitude—not of mimesis, so-called… “realism” but rather the experience of being itself… of simply being a human being.

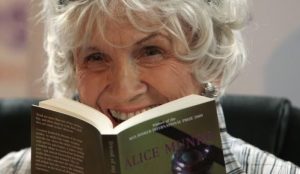

Many critics have noted that Munro’s stories frequently have the emotional and literary depth of novels.

Some people have questioned whether Munro genuinely writes short stories or novels.

Alex Keegan, writing in Eclectica, said simply: “Who cares?” Most Munro stories include as many as several novels.

Research on Munro’s work has been ongoing since the early 1970s, with the first PhD thesis published in 1972.

The Art of Alice Munro: Saying the Unsayable, the first book-length compilation containing the talks presented at the University of Waterloo’s inaugural symposium on her work, was released in 1984.

In 2003/2004, the publication Open Letter, a Canadian quarterly review of writing and sources, published 14 articles on Munro’s work.

In 2010, the Journal of the Short Story in English (JSSE)/Les cahiers de la nouvelle dedicated a special issue to Munro.

In 2012, an issue of the journal Narrative focused on a single story by Munro, “Passion” (2004), including an introduction, a description of the story, and five analytical articles.

Generating new versions

Munro published multiple versions of her stories, sometimes in a short period.

Her stories “Save the Reaper” and “Passion” were published in two distinct versions in the same year, 1998 and 2004, respectively.

Two further pieces, “Home” (1974/2006/2014) and “Wood” (1980/2009), were reissued in different editions around 30 years apart.

In 2006, Ann Close and Lisa Dickler Awano stated that Munro refused to reread the galleys of Runaway (2004), saying, “No, because I’ll rewrite the stories.”

In their symposium contribution An Appreciation of Alice Munro, they argue that Munro produced eight versions of her novella “Powers”, for example.

According to Awano, “Wood” is a good example of Munro, “a tireless self-editor,” rewriting and revising a story, in this case returning to it for a second publication nearly 30 years later, revising characterizations, themes, and perspectives, as well as rhythmic syllables, a conjunction, or a punctuation mark.

Characters also change. According to their perspective, they were middle-aged in 1980 and elderly in 2009.

Awano observes a heightened lyricism caused not least by the lyrical clarity of Munro’s rewriting.

The 2009 version features eight portions, compared to three in the 1980 original, as well as a new ending.

Awano adds that Munro actually “refinishes” the first take on the story with an ambiguity characteristic of her endings.

Munro reimagines her stories throughout her work in numerous ways.

Alice Munro’s Personal Life

Munro married James Munro in 1951.

Their daughters, Sheila, Catherine, and Jenny, were born in 1953, 1955, and 1957, respectively; Catherine died on the day of her birth owing to kidney failure.

The Munros relocated to Victoria in 1963 and established Munro’s Books, a well-known bookstore that is still in operation today.

In 1966, their daughter Andrea was born.

Alice and James Munro got divorced in 1972.

Munro returned to Ontario to serve as writer-in-residence at the University of Western Ontario, where he received an honorary LLD degree in 1976.

In 1976, she married Gerald Fremlin, a cartographer and geographer she met at university.

The couple moved to a farm outside Clinton, Ontario, and then to a residence in Clinton, where Fremlin died on April 17, 2013, at the age of 88.

Munro and Fremlin also had a residence in Comox, British Columbia.

Sheila Munro’s childhood memoir, Lives of Mothers and Daughters: Growing Up With Alice Munro, was released in 2002.

In 2009, Munro announced that she had received therapy for cancer and a cardiac issue that required coronary artery bypass surgery.

Alice Munro Death

Munro, 92, died at home in Port Hope, Ontario, on May 13, 2024. She had been suffering from dementia for at least twelve years.

Alice Munro Legacy

Munro’s work has been described as reinventing the architecture of the short story, particularly in its inclination to go forward and backward in time, as well as with interwoven short fiction cycles in which she demonstrated “inarguable virtuosity”.

Her stories have been described as “embed more than announce, reveal more than parade”.

Munro was regarded as a pioneer in short story writing, with the Swedish Academy describing her as a “master of the contemporary short story” who could “accommodate the entire epic complexity of the novel in just a few short pages.”

Her writings and career have been compared to those of other well-known short story writers, like Anton Chekhov and John Cheever.

In her obituary in The New York Times, Munro’s works were recognized for “attracting a new generation of readers” and labeled her a “master of the short story”.

Her work has been dubbed a “national treasure” for Canada because it focuses mostly on life in rural Canada through the lens of women.

Fellow Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood described Munro as a “pioneer for women and Canadians.”

According to the Associated Press, Munro “perfected one of the greatest tricks of any art form: illuminating the universal through the particular, creating stories set around Canada that appealed to readers far away.”

Munro’s works, according to Sherry Linkon, a Georgetown University professor, “helped remodel and revitalize the short-story form”.

The complex issues tackled throughout the written works, such as womanhood, mortality, relationships, aging, and themes linked with the Counterculture of the 1960s, were considered pioneering, especially since they were able to be captured in the short story form.

When she won the Booker Prize, the committee’s assessors hailed her works as “[bringing] as much depth, wisdom, and precision to every story as most novelists bring to a lifetime of novels”

Alice Munro Facts

Alice Munro, a critically acclaimed Canadian short-story writer, earned the Man Booker International Prize in 2009 and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013.

Alice Munro was the first Canadian woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Alice Munro is the first Canadian writer to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature since 1976 when Saul Bellow won.

Alice Munro is the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature since Herta Mueller in 2009.

Alice Munro is just the 13th woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature since its inception in 1901.

Alice Munro Bibliography

2014: Lying Under The Apple Tree: New Selected Stories

2012: Dear Life.

2009: Too much happiness.

2006: Carried away.

2006: View from Castle Rock.

2004: Runaway.

2001: Hatred, friendship, courtship, love, and marriage.

1999: Queenie: A Story.

1998: Love of a Good Woman.

1996: Selected Stories

1994: The Wilderness Station

1994: Open Secrets.

1990: Friend from My Youth

1989: Best American Short Stories.

1986: Night Light: Stories on Aging

1986: The Progress of Love.

1983: The Moons of Jupiter: Stories.

1978: Who Do You Think You Are?: Stories.

1977: Personal Fictions: Stories by Munro, Wiebe, Thomas, and Blaise, selected by Michael Ondaatje.

1977: Here and Now.

1974: Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You: Thirteen Stories

1974: Narrative Voice: Stories and Reflections by Canadians

1977: Here and Now.

1974: Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You: Thirteen Stories

1974: The Narrative Voice: Stories and Reflections of Canadian Authors

1973: The lives of girls and women.

1970: Sixteen by Twelve: Short Stories by Canadian Authors

1968: Dance of the Happy Shades.

1968: Canadian Short Stories.

Alice Munro Awards

2013: Nobel Prize for Literature

2009: Man Booker International Prize.

2007: Commonwealth Writers Prize (Best Book from the Caribbean and Canada region)

2007: James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction.

2007: Man Booker International Prize (Nominee)

2005: Commonwealth Writers Prize (Africa Region; Best Book)

2004, Giller Prize (Canada)

1998: Giller Prize (Canada).

1995: The Irish Times International Fiction Prize.

1995: WH Smith Literary Award.

1990: Canada Council Molson Prize

1990: Commonwealth Writers Prize (Best Book from the Caribbean and Canada)

1990: The Irish Times International Fiction Prize

1990: Ontario Trillium Book Award.

1986: Governor General’s Literary Award in Fiction (Canada)

1986: Marian Engel Award (Canada).

1980: Booker Prize for Fiction (shortlisted)

1978: Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction (Canada).

1977: Canadian-Australian Literary Prize

1971: Canadian Booksellers Association Award.

1968: The Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction (Canada)

Alice Munro Quotes

I hope that this will help people perceive the short story as a serious art form, rather than something to toy about with until you’ve written a novel.”[Upon accepting the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature.]

It’s wonderful to end with a bang.”[About receiving a Canadian Book Award for “Dear Life.”]

I knew I was in the running, but I never expected to win.”[Upon accepting the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature.]

Who Is Alice Munro?

Alice Munro, a writer best known for her short stories, was born in Canada in 1931.

She attended the University of Western Ontario.

Dance of the Happy Shades was her first collection of stories to be published.

Munro took home the Man Booker International Prize in 2009.

That same year, she released the short tale collection Too Much Happiness.

Munro, 82, received the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature.

What exactly is Alice Munro’s writing style?

Much of Munro’s work represents the Southern Ontario Gothic literary type. Munro’s work is frequently compared to the great short-story authors. The plot of her works, like Chekhov’s, is secondary, and “little happens”.

Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize for what?

Munro was recognized as “a master of the contemporary short story” when she received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013, a year after publishing her final collection, “Dear Life.”

What are some fascinating facts about Alice Munro?

She was born Alice Laidlaw on July 10, 1931, in Wingham, Ontario. Munro was raised on what she describes as a “collapsing enterprise of a fox and mink farm.” 2. Munro began writing short stories because, as a mother with three young girls, she did not have the time to devote to a novel.

How many short stories did Alice Munro write?

In awarding her the Nobel Prize in 2013, when she was 82, the Swedish Academy praised her 14 collections of stories and referred to her as “a master of the contemporary short story,” complimenting her ability to “accommodate the entire epic complexity of the novel in just a few short pages.”

What are the defining characteristics of Munro’s short story writing?

Munro’s style juxtaposes the personalities, allowing the reader to distinguish between them. Throughout the novel, she describes characters in the same paragraph or even sentence.

What is the overall topic of Alice Munro’s short stories?

The overall topic of the stories is women’s lives, how they live and think, and how they challenge the expectations of family, friends, and society. The stories also explore issues such as treachery, desertion, and vulnerability.

What was Alice Munro’s age when she won the Nobel Prize?

The Swedish Academy announced the honor in Stockholm, describing Ms. Munro, 82, as a “master of the contemporary short story.” She has written 14 story collections. She is the thirteenth woman to win the prize.

Discover more from Labaran Yau

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.